A Lesson in Creativity

Human creativity is one of science’s enigmas. On top of its mysterious origin, it is also distributed unevenly among the population. Most individuals go through their lives without a notable creative contribution to society; whereas a minority of outliers come up with revolutionary ideas, inventions and works of art. But even those outliers are not creative all the time. They have “miracle years”, “golden decades” and “creative climaxes”. Some create their magnum opuses in their twenties, some in their thirties and some even in their sixties.

In the past century, four such individuals rose to international superstardom and became the greatest band in the world. Their entire output happened in less than 10 years, yet it changed the world forever. Despite their creative genius, the Fab Four weren’t equally creative all the time. I would argue their art grew along with their cognitive disinhibition.

Cognitive Disinhibition

Between our ears sits an information processing machine. Despite its unprecedented power in the animal kingdom, the human brain processes a tiny fraction of all the data rushing towards it from the senses. Filters within the brain select the most important information for our survival and broadcast it into our conscious experience. The rest remains swirling in subconscious space.

Cognitive disinhibition happens when our mind-filters leak. Thus, seemingly irrelevant information makes its way into consciousness. Throughout their lives, creative individuals use those leaks to create unique connections between unrelated concepts. Yet, if the filters get too punctured, the flow of useless data becomes overwhelming and the mind spins into mental illness. Thus, creative breakthroughs happen on a delicate balance.

During moments of insight, cognitive filters relax momentarily and allow ideas that are on the brain’s back burners to leap forward into conscious awareness, […] — Carson, 2017.

Whether they knew it or not, the Beatles reached new peaks of creativity as their cognitive filters relaxed and multiplied the lanes in the highways of their minds.

Boys singing about Girls (1962–1964)

I wanna be your lover baby/I wanna be your man/Love you like no other baby/Like no other can — Lennon-McCartney (1963)

For the first few years of their career, the Beatles wrote exclusively boy-loves-girl or girl-loves-boy songs. That subject is safe, universal and — if there’s a good rhythm to it — sells millions or records. They wrote material that resonated with crowds of girls attending their concerts. The few songs unrelated to love on their early albums were covers of work by more mature songwriters.

Did it get corny sometimes? Sure. But who could blame them? They were young, ambitious and full of testosterone. Their male biology and their creativity frolicked hand in hand. They had all their ideas in one winning formula.

At the onset of their career, the record industry had much more influence on their work. They had to write songs that sold. The Beatles were there to “please please us”! They were “for sale”! Their writing was limited to songs the four of them could perform on stage. Their exhausting touring schedule did not allow for prolonged sessions of creativity in the recording studio.

During this period, the Beatles still managed to create masterpieces like “Yesterday” and “Ticket to Ride”. Yet, by their fourth year of stardom, they were screaming for Help!

My independence seems to vanish in the haze/ But every now and then I feel so insecure/ I know that I just need you like I’ve never done before — Lennon-McCartney (1965)

Turning the Corner (1965–1966)

Though I know I’ll never lose affection/For people and things that went before/ I know I’ll often stop and think about them/In my life, I love you more — Lennon/McCartney (1965)

By 1965, the Beatles had met Bob Dylan, who introduced them to pot. George, John and Ringo had also had their first LSD trips (Paul would join a year later). Their cognitive disinhibiton was growing with the help of psychedelics.

Rubber Soul, their sixth studio album, turned a creative corner. The Beatles introduced new instruments to their musical arsenal: the sitar, the harmonium and the fuzz bass. Their lyrics became more nuanced and poetic. The high-quality of every song on the record ushered the “Album era” of popular music. The Beatles demonstrated that an album could be a work of art from beginning to end instead of a couple of hit singles drowning in filler. From then on, they would produce original material only, no more covers (until “Maggie Mae” in 1970)!

“We’d had our cute period, and now it was time to expand.” — Paul McCartney

As the others retired to the countryside to have a break from Beatlemania, Paul stayed in London. He became the link between the Beatles and the progressive art world. Thus, the band became aware of prominent counterculture ideas by figures such as Alan Ginsberg and Timothy Leary. The landscape of possible music was growing wider and more colorful.

In 1966, the Beatles put out their seventh album: Revolver. By that point, they were no longer concerned with reproducing their new songs live. Their experimentation pushed further than ever. “Eleanor Rigby” was supported by a string-octet. “Yellow Submarine” included sound effects such as : clinking glasses, rattling chains and Lennon blowing bubbles in a glass of water (oh, and the song is about life on an imaginary yellow submarine!). The studio became an instrument in the Leary-inspired track “Tomorrow Never Knows”. The band used tape loops, reversed guitar, tambura, artificial double tracking vocals and many more studio effects to conjure a psychedelic state within a song.

Despite the myriad of new textures in their songs, the Beatles never used an effect simply to show off. Their lyrics and their sounds merged seamlessly to convey a deeper meaning. All the tricks were subordinate to a central idea, not the other way around.

Shortly after the release of Revolver, the Beatles embarked on their last tour. They played none of their new songs. And little did it matter; the hordes of fans could hardly hear anything through their own relentless screaming.

After more than 1 400 concerts, the group chose the recording studio as the only proper outlet for their creativity.

“send out four waxworks … and that would satisfy the crowds. Beatles concerts are nothing to do with music anymore. They’re just bloody tribal rites.” — John Lennon, 1966.

By the end of 1966, the Beatles would lock themselves in Abbey Road studios to create the most original work of popular music ever made.

But listen to the color of your dreams/It is not living? it is not living?/So play the game “Existence” to the end…/Of the beginning… — Lennon/McCartney (1966)

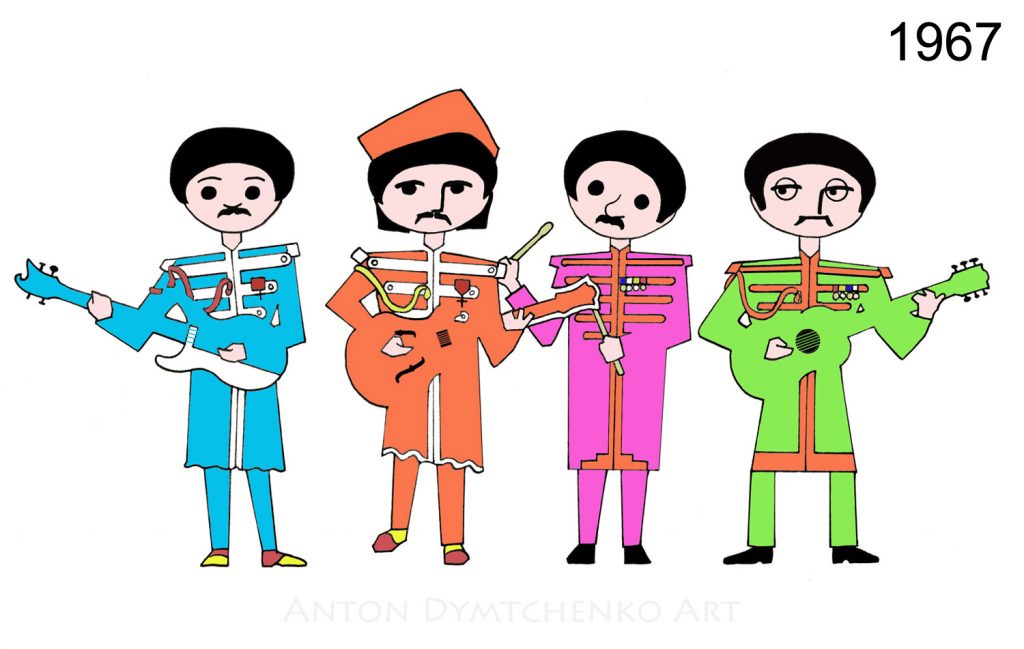

Creative Climax (1967–1969)

Picture yourself in a boat on a river/With tangerine trees and marmalade skies/Somebody calls you, you answer quite slowly/A girl with kaleidoscope eyes — Lennon/McCartney (1967)

In 1967, the Beatles achieved a high-point of creative disinhibition by concocting an alter-ego group for whom everything was allowed. Ideas were no longer filtered by the minds of the Fab Four, they were filtered by Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Nothing was out of reach for the imaginary quartet.

At this new creative level, John was able to gestate an entire song — based on a drawing by his son — about a girl with kaleidoscope eyes. Paul let his mind wander in “Fixing a Hole” (where the rain of outside influence gets in). George conveyed a spiritual journey in“Within You Without You”. Ultimately, one of the greatest Lennon/McCartney collaborations, “A Day in the Life”, brought the album to its climax with its dream sequence and the atonal crescendo performed by a 40-piece orchestra.

The opus took 700 hours to complete (compare that with the 12 hours it took for their first record, Please Please Me in 1963). Needless to say, the band used many uncommon instruments including: the Mellotron, the Lowrey organ and the harpsichord. Upon its release, the album was universally hailed as the greatest work in popular music.

The Beatles’s journey through the looking glass continued in the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack. They sung about the most unexpected subjects such as: being a walrus, a fool on a hill, strawberry fields and a whole song about saying “hello” and “goodbye”. Not to mention the international anthem of the Summer of Love: “All You Need is Love”. If you haven’t heard of it, your mother should know.

In 1968, the group pushed their artistic introspection even further by attending a three-month meditation course by Maharishi Yogi in Rishikesh, India. Even though they were ultimately disappointed by their guru, the experience laid the groundwork for most of the 30 tracks on their upcoming double-album.

The whiteness on the cover of The Beatles album evoked a blank page on which anything could be written. Paul wrote a song about his sheepdog, Martha. John imagined a warm song about happiness after seeing an advertisement for guns. George shared the weeping of his guitar (with a bit of help from Eric Clapton, of course).

The Beatles were still riding high on their creativity, yet, their unity was breaking down.

After the unfinished Get Back sessions in 1969, they decided to split on a high note an recorded their last work: Abbey Road. The album began with individually written masterpieces such as “Come Together”, “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun”. It ended with a medley of short songs strung together in a peculiar unity. Abbey Road was the synthesis of the Beatles’s art. It was out-of-the-box, yet not as phantasmagorical as their three previous releases. Their rock-n-roll roots came back in the mix. They didn’t write to please, yet they didn’t pretend to be someone else to be truly creative. They had finally found a stance with one foot on reality and one through the looking glass.

In 1970, the Get Back sessions were remodeled into the Let It Be album on which John Lennon left us his most poetic lyrics:

Words are flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup/ They slither while they pass, they slip away across the Universe/Pools of sorrow waves of joy are drifting through my opened mind/Possessing and caressing me — Lennon/McCartney (1969)

In the end, the Beatles tried every available method to expand their cognitive disinhibition: psychedelics, counterculture ideas, progressive art, new instruments, alter-egos and meditation. Yet, their most useful asset was their collaboration. Four highly creative individuals multiply their impact exponentially when they bounce ideas off of each other. We can only be grateful that they happened to meet at the right time.

Reference: Carson, Shelley. “The Unleashed Mind” Scientific American Mind, Spring 2017.

Further reading: